Any person who has ever entered the gym will recognise the testosterone that permeates from the dreaded ‘free weights zone’. There are men who choose to emphasise their ownership over this place by collecting an array of different sized weights and placing them unused around their bench- as if it were a perimeter guarding their home. This is the perfect example of a ‘gendered space’; ‘areas in which particular genders of people, and particular types of gender expression, are considered welcome or appropriate, and other types are unwelcome or inappropriate’.

As mentioned in previous posts, place is a space that we, as humans, have created an identity for and developed a relationship with. Place is very personal. Perceptions and boundaries of place differ between those experiencing and interacting with it. However, as humans have created places for living, working and socialising in many cultures, these places have often been gendered: designated for either women or men.

Gender, in traditional western society, has been considered as a binary identity: either male or female. The LGBTQ+ community have helped pull apart this concept by discussing, much like sexuality, gender to be fluid. Regardless, many places still exist that are ‘gendered spaces’.

Japan’s Gendered Places

Japan’s gendered workspaces

Japan in many ways is still a very traditional society where white-collar professionals (or ‘salary men’ as coined in Japan) are typically men. Even the term ‘salary men’ is exclusively male, and to my understanding, a female equivalent is not used. This is evidently seen in Shinjuku Station (one of the busiest in Tokyo) at rush hour, where there is a sea of near-uniformed men all in suits lining up in military precision to board trains to reach their places of employment.

This workplace consistency enacts a Japanese saying ‘the nail that sticks out is the first to get hit’; promoting what is harmonious with the norm whilst undermining what is not. The idolisation of uniformity in Japan can be extended to work-place culture, reinforcing a Japanese version of ‘toxic masculinity’. This manifests in the stereotypes that a man’s most significant role is in the workplace. Resulting in a male culture that includes expectations of extremely long hours, reinforced by commending those who have fallen asleep at work due to exhaustion (Guardian, 2014). This has been linked to the high suicide rates of Japan; 17th highest in the world in 2016, 15th when solely considering men (GHO, 2016). Although the workplace may appear initially more inviting for men due to their dominance over this space, the expectations put upon them may make the environment hostile.

As recently as 2013, only 60% of working-aged women were employed, compared to 80% of men. However, as of August 2018, this has increased by 10% (Asian Review, 2018). The comparatively new transition is due to a declining working-age population, providing greater opportunities for women to infiltrate this already male-dominated environment. This is not apparent when walking around the business districts of Tokyo, female workers are uncommon in professional environments. ‘Four out of five listed companies in Japan have no women on their boards of directors. This puts the country in company with Saudi Arabia, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates as one of the worst when it comes to diversity‘. Asian Review identifies the demand for women for more menial administrative positions and part-time jobs that allow them to uphold their traditional household and family rearing roles. Whilst Japan has made headway, gendered workplaces remain commonplace.

Japan’s Gendered Social Spaces

Japan’s place gender divide is not limited to the workplace but is also present in spaces used for after-work socialising. Japan has a heavy drinking culture with tea houses and bars, known as Izakaya. In my personal experience, the majority of the Japanese patrons remained largely, if not exclusively, male. Whether the women were officially uninvited or did not feel welcomed, is unclear. Regardless, within Japan, these places are still frequent watering holes of the diligent business men of Japan.

There are areas within Japan that, although not solely designed for men, invite-only women that fall into specific criteria. For example, Tokyo’s anime district Akihabara, where the streets are lined of 9-floor Anime and Manga super-stores. The women portrayed in these cartoons are unrealistically over-sexualised and the female employees fulfil this perception. The women here, other than a few Anime mega-fans, are dressed in cute anime character outfits inviting potential customers to enter ‘maid cafes’. The hostesses’ real life depiction of Anime reinforces the stereotype that women’s greatest asset is their sexuality. Is this a combatant force against the patriarchy or an act of submission? In this example the place has not been created for equal use for women and men; men are the consumers within it whilst women are employees, enacting the male gaze’s fantasy.

Just as Japan has specific male-dominated spaces, there are also those exclusively for women; the Onsen. Onsen are public spring baths that have separate spaces for women and men. Largely, this is due to the desire to maintain dignity and tradition, as swimming costumes are prohibited, thus all bathers remain nude. However, this safe place for women has created communities for centuries. It was until as recently as the 1950s that the majority of Japanese solely used bathhouses to bathe instead of washing at home, and for a large proportion of citizens, it is still preferable. Within the Onsen women comfortably bathe, relax, catch up with old friends and have a good old gossip. Within the Onsen, there is no male gaze to interfere with or dictate expectations of women’s bodies or their behaviour. Thus allowing women to create their own culture safe for restraint, or anxiety from female consumers about whether their behaviour satisfactory for a male-dominated society. In a country where there are few places designed for women, this remains a sanctuary

Non-Gendered Places within the UK

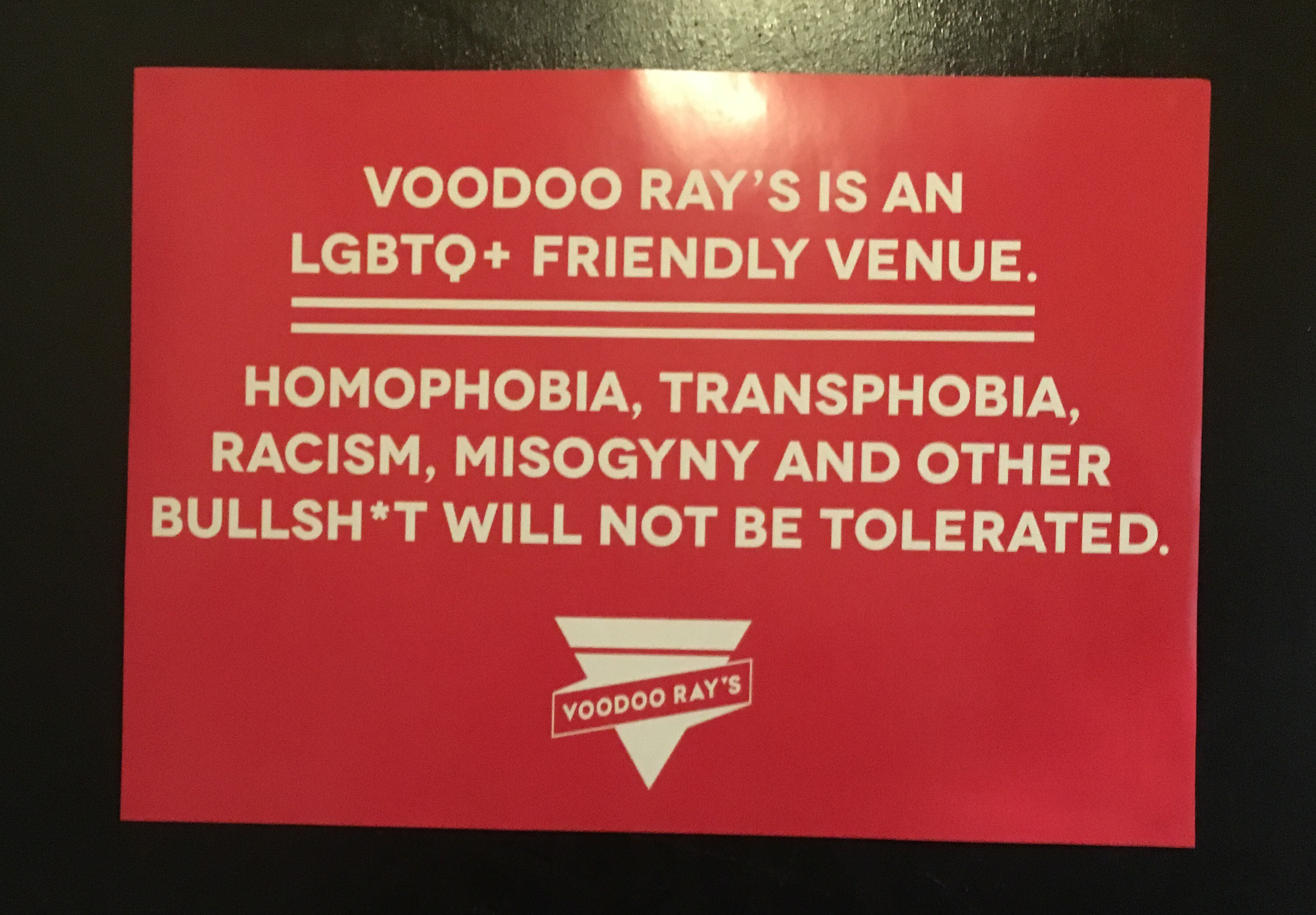

In country’s where gender equality is more evident and there is increasingly more awareness of gender fluidity, gendered spaces are being juxtaposed. This can simply be seen in areas such as gendered toilets being questioned, to be more accepting for non-binary and trans customers and employees. Pizza restaurant chain Voodoo Rays has gender-neutral toilets at their Dalston branch. Their message about recognition and acceptance for all regardless of their gender and sexual identity has been recognised online and is evident with the posters in their toilet.

The only opposition for making toilets an example of gender-neutral spaces has been that they do not benefit cis-women. Historically, there have been fewer toilets available for women, due to designers having a male-centric view of the demand and use of toilets (women are unable to use urinals and therefore more toilets are needed). Some argue that by making these spaces inclusive to all genders, the protection of women and their safety, dignity and privacy is disregarded. Furthermore, the desegregating of public toilets also excludes women from conservative religious backgrounds that forbid sharing toilets with male strangers whilst menstruating.

Food for thought

Is there still a purpose or worth of gendered spaces?

If so where do these spaces exist?

What are the impact on different genders if gendered spaces continue?

Does having separate spaces for different genders lead to the other gender/s being seen as ‘other’ or ‘alien’?

Where is there a need to remove gendered spaces?

How can this be done that the spaces are inclusive but ensure respect for all genders that use the space?

This post has discussed suicide. If hearing about suicide has raised any concerns for you, please reach out and talk to someone i.e. here.

some times its a pain in the ass to read what people wrote but this website is really user pleasant! .

LikeLike

very good publish, i actually love this web site, carry on it

LikeLike

This design is incredible! You most certainly know how to keep a reader amused. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

LikeLike

I am impressed with this internet site, rattling I am a big fan .

LikeLike

some truly choice posts on this web site, bookmarked.

LikeLike

I am impressed with this web site, very I am a big fan .

LikeLike